Shaw was inherently suspicious of women bearing celery, even more so when they came wrapped up with a ‘detect-by-numbers’ investigation and a pre-conceived definition of success. Dinah, however, was less wary, more than willing to waive all objections aside with a fan formed of £1,000 in crisp twenties and the promise of much more to come. “It sounds so easy,” she reasoned after the woman had departed. “I think you’ll be really good at it.” Shaw remained doubtful, particularly given the slight implication that if it had been anything other than easy, he almost certainly would not ‘be really good at it’. “We can pay off all of our debts,” Dinah pressed on, “and stop hiding from the landlady. I might be able to buy some underwear that doesn’t come from Poundland and you might be able to buy those boots you like if she coughs up the bonus…” Shaw liked the sound of the bonus, although he couldn’t help thinking that this was the first time he had heard mention of it. He remained suspicious. Why was celery woman so free with her cash, so insistent on this being ‘strictly a one person assignment’, so particular with her nitpicking ‘do’s and don’ts’? (Particularly, Shaw noted bitterly, the don’ts.) Why had she chosen them when she could so patently afford an agency altogether more suited to this kind of ‘mainstream’ investigation: someone, perhaps, with a car to sit in, a proper box for their sandwiches and a notepad to write on? But Dinah seemed so lifted by the prospect of pecuniary buoyancy that he didn’t have the heart to question her…

…It was one of those dawns when the pale, sickly sunshine actually cooled the atmosphere. Tiny pin-pricks of rain that hung, twisting like a veil, falling from who-knows-where, cast glistening frozen rainbows against the slate grey backdrop of the sky. Early morning commuters shuffled by, hunched in winter overcoats and hand-knitted mufflers, cursing the jobs that drew them so prematurely from their already cooling beds. On the corner by the bin, under the recently extinguished streetlight, Shaw pulled the collar of his ragged, threadbare jacket over his ears and regretted with every fibre of his emaciated body that vanity had forced him to turn down Dinah’s offer of an oversized pink cashmere cardigan to wear under his see-through tweed on the grounds that he would never be that cold, because he very patently now was.

Across the road, the third floor curtains remained tightly shut, as they had been since 6pm the previous evening. It had been a long night for Shaw and his attention was beginning to flag. His shallow well of enthusiasm had become the victim of severe drought and his mind was filled with the memory of the hipflask he had carefully laid out in preparation for his ordeal, but stubbornly refused to bring along when he discovered that they had nothing more warming than Ribena to put into it. The brown paper sandwich bag that Dinah had lovingly filled for him was now empty and his meagre supply of patience had eroded away like a talcum motorway. Also, the situation within his bladder was becoming close to critical.

He had managed, unobserved, to relieve himself behind a low box hedge at three a.m., but there were far too many people around now to try that again: stooping down was now completely out of the question as his knees were giving him merry hell already. Anyway, there were limits to what he would do for cash in hand and being arrested for indecent exposure was well beyond all of them. Besides, he was so cold he could barely feel his fingers and he knew he would not be able to trust them to open his zip until they had warmed a little, let alone close it before the regular stream of cockapoo walkers started parading by. Not pulling the fly back up was bad enough, but not getting it down in the first place was a risk too far. He figured he had about thirty minutes before he would have to find an early morning café which might let him use their staff lavatory in return for the purchase of a mug of thrice-brewed tea, a dog-eared sausage bap and his attendance at a thirty minute lecture on ‘the trouble with foreigners’ from the Turkish owner. Half an hour and not a minute longer: whatever the client had stipulated, that was his limit. He would tell Dinah that he had been chased from his post by a pack of rabid urban foxes or a mackintoshed nanny with two identical en-prammed babies and a screaming toddler in Unicorn wellington boots.

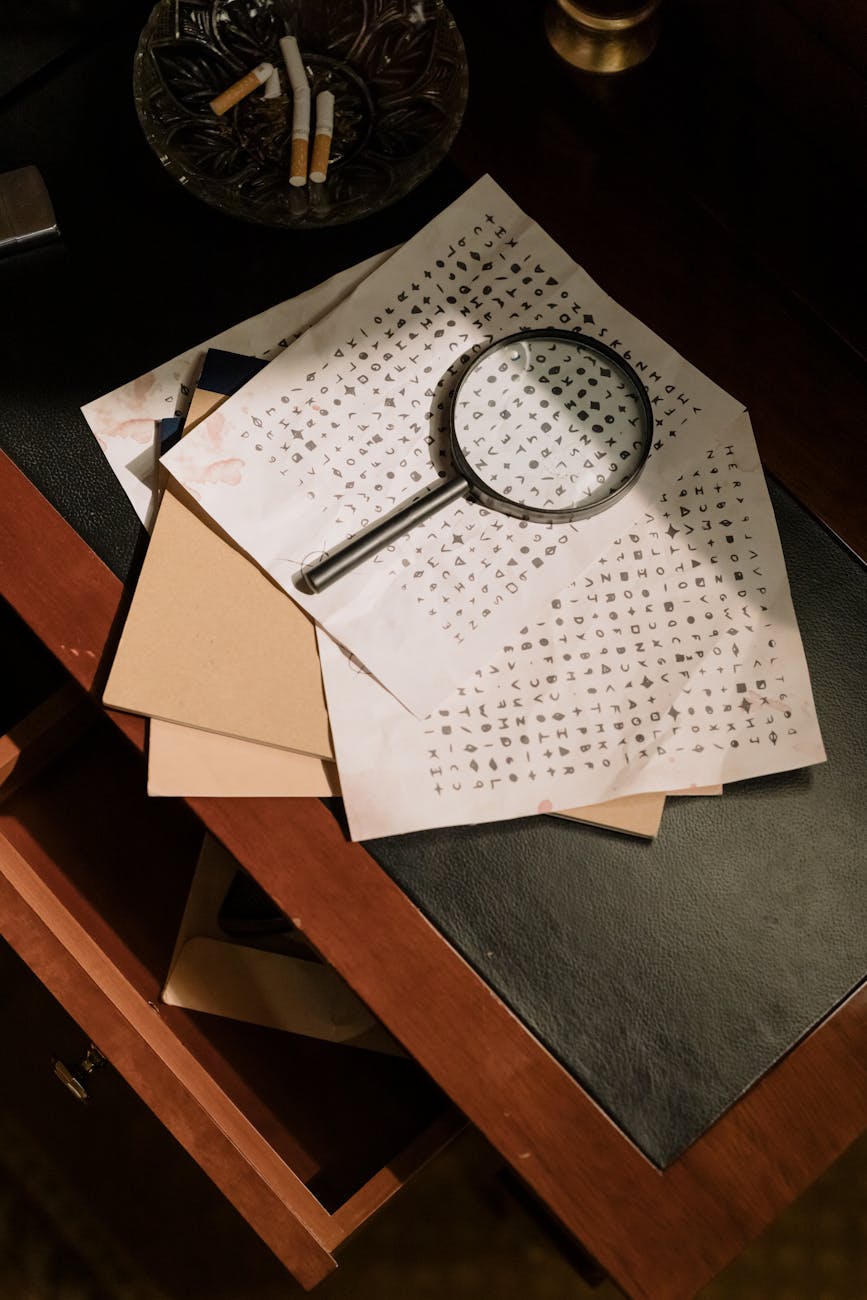

The client’s stipulations had, in fact, occupied his mind through much of the night. A thousand quid in cash was never to be sniffed at, even he would concede that, but the whole set-up was exceedingly odd. A black and white photograph of a building – the building he had been watching all night – with a window circled in red. On the back a scribbled note directing him to watch the window from 5pm and to report back with the time the curtains closed, and the time they re-opened. Nothing to report in between, but no prospect of any further payment if he failed to note the exact time of either. Why? He couldn’t help but wonder how they would ever know that he hadn’t just made them up – unless they were watching him.

The curtains had, in fact, closed at 6pm. It was a woman who closed them, he could see that, and he presumed that whoever she was, she had only recently entered the flat because the light had come on just moments before and she was still wearing a coat. Unless, of course, she had been there all the time and had just put her coat on to leave. Although why would she put the light on if that was the case? Security? On the third floor? Shaw doubted that. To throw him off the scent? How could she even know that he was there? He’d only been on the corner for an hour by that stage. This was a London street. He would have to have been there for weeks before anybody noticed him… and dead probably. He seriously doubted that anyone in this neighbourhood would raise the alarm even then. Short of blocking access to the Waitrose Delivery Van, there was little he could do to impinge upon the consciousness of these people.

Anyway, the client did not want to know anything other than the precise times that the curtains closed and opened. Really odd. It was quite specific. Not the times that anybody entered or left the flat, just the curtain opening and closing times. Shaw was willing to concede that watching out for people entering or leaving would have been more tricky – a little work on the pin-entry system or a shy, lost smile for a co-tenant – but definitely achievable and certainly warmer.

It was at about 4am, in that brief window between the latest of home-comers and the earliest of early-risers, that an uneasy suspicion had begun to settle upon him. Just suppose that it was not about the people in the flat at all? Suppose it was about him. Suppose it was all about watching him. He had to stand where he was in order to keep the window in view. The woman who had paid the money would know exactly where he would be for an extended period of time and she would know immediately if he had not done what he had been paid to do. It was that realisation alone that had kept him there these last two hours. It could all be a test. Shaw had never been great at tests, and he had never had to report the results to Dinah before, so he resolved that come what may (excepting, perhaps, an extreme urinary crisis) this was a test he would pass.

And then he thought again about the set-up: what if that was exactly what it was? Incriminating someone when you know exactly where they are and what they are doing; when you know that they have no idea why they are there, nor who sent them, and no alibi that could – even in Shaw’s world – be deemed at all reasonable, would be piece of cake.

He decided that the time to move on had come. The curtains might never open – that could be the plan. He’d earned the money by now. They could come and claim it back – from Dinah – if they felt differently. They would have to admit they had been watching him and they would have to explain exactly what was going on. He crumpled his paper bag and dropped it into the bin before taking one final glance up at the window, registering immediately that the curtains had opened, just a crack, revealing that the ceiling light was still on behind them. He resolved in that second to that he would go and ring the flat’s intercom. (He had spent much of the night working out what number it must be and he was almost certain that it was very much probably 23… or 18… or if the flat below had an extra bedroom, 27…) He would demand that whoever answered should explain exactly what was going on here. And he would have done so too, if the sudden, friendly wave from the now unadorned window had not completely caught him off guard and coincided so precisely with the flashing pain across the back of his skull…

I originally wrote this little vignette for my Writer’s Circle thread (episode 6 – The Point, published 20.02.2021) but had somehow filed it in my head as a missing Dinah & Shaw story. When I found it and read it through, I realised that it really should have been about these two, so I set about re-writing it…

Lovely atmospheric write Colin. Shaw shows all the paranoia a good ‘tec needs. How ironic for the poor chap that just as he gets a sliver of enlightenment the lights go out. Poor sap.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Uh-oh! Poor Shaw. Just when he was asking all the right questions. I will be waiting anxiously for pat two.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Coming Wednesday 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! I LOVE this one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 😊

LikeLike